In 2021, the number of animals used for research testing in South Korea reached a record high of 4.8 million. This trend of increased animal testing in South Korea cuts against the global trend of development and adoption of innovative, non-animal approaches—the New Approach Methodologies. Despite its current reliance on animals, South Korea is actively involved in the pursuit of innovative approaches including organ-on-a-chip technology, organoids and computer-based modelling. However, wider adoption of NAMs is slow and could be accelerated through stronger harmonization of efforts involving regulatory authorities and other stakeholders.

To provide the legislative support needed to advance the use of of NAMs, HSI/Korea has been working with lawmakers, researchers, and industries to pass the PAAM Act. This bill, the Act on the Promotion of Development, Dissemination and Use of Alternative to Animal Testing Methods, was introduced in 2020 at Korea’s National Assembly by Assemblymember Ms. In-soon Nam.

As a part of ongoing efforts to raise stakeholder awareness around the PAAM Act and the need for wider adoption of NAMs, HSI/Korea’s director of government affairs, Borami Seo, spoke to Dr. Lorna Ewart, chief scientific officer at Emulate, Inc. Emulate produces human cell-based technologies that recreate human biology, Organ-Chips, also known as microphysiological systems. We asked Dr. Ewart to explain how these technologies can shift the paradigm of health research toward more human-predictive methods.

HSI: For those readers who are unfamiliar with organ-on-a-chip technology, could you briefly explain what it is?

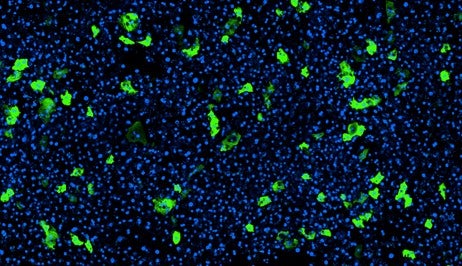

Lorna Ewart: OOC is an in vitro model that allows cells to exist and function as if they were in the human body. We believe that if the cells are in an environment familiar to them, they will function like they would in the human body. Therefore, the data we generate from these models, can be translated into whole human body response, increasing the translational value of the data.

HSI: OOC is still a new technology. What are the challenges that you have been facing?

Lorna Ewart: At Emulate, we see five major challenges. One, scientists need to be convinced that the microfluidic platform is robust and reliable. Now that we can show this, the next challenge is sourcing good quality human cells. Cell quality is a challenge for the industry at large, but it is important because good cells make good models, and this equals good data. The third challenge is ensuring that we reduce the complexity of operation. We want to make it as easy as possible for scientists to work with our instruments to generate data. The next challenge would be answering the question, “Why bother using organ-chips when there are other methods?” We need to demonstrate the value of data generated using OOC. Lastly, there are many organizations developing OOC models. Engineers are building diverse microfluidics platforms or designing different chips. Many people in this field believe that having different types, shapes and sizes of instruments or chips is slowing the field down. Therefore, there are many discussions around the standardization of the technology which will accelerate adoption and ultimately commercialization of OOC, but standardization too soon may reduce overall innovation.

HSI: What are the prospects of OOC? How far has the commercialization process come?

Lorna Ewart: At Emulate, we work with academic researchers, scientists in the pharmaceutical industry, and government agencies, predominantly the US Food and Drug Administration. Those scientists are either using models that we have developed or we train them to build their own models. Emulate currently has validated workflows and applications for five major organs: the liver, the colon intestine, the duodenum intestine, the brain and the kidney. However, our customers have built over 70 various combinations of models and applications.

In terms of commercialization, Emulate began to be commercially active in 2018. We sell the Human Emulate System, which includes the chips, the microfluidic instrument, software and accessories needed for scientists to use OOC in their research. If researchers want, they can also buy cells from Emulate, which we call a “Biokit,” across the five organ models we are building. Or customers can buy chips that are compatible with the microfluidic instrument and build models using their own cells. We also perform fee-for-service studies where customers ask us to perform the experiment on their behalf, often involving one of their assets.

HSI: For regulatory adoption, standardization seems to be the next step. How does it work with regulators?

Lorna Ewart: The US and EU regulatory authorities welcome the fact that OOC platforms represent a credible approach to animal models. They are specifically interested to learn if these new models can provide data that closely resemble human responses and that they are reproducible and reliable.

Regulatory authorities want to understand the relevance of the data that OOC can provide. This is because they are primarily interested in safety data generated from OOC. The regulator’s role in progressing candidate drugs into clinical trials relies on demonstrating that it is safe for humans. In subsequent phases of clinical development, efficacy is of paramount importance. Models that show a high degree of human relevance will give the regulators greater confidence to progress the candidate drug into the clinic. We should also remember that regulators also want confidence in drug efficacy and OOC can also be used for this purpose and may also reduce the use of animals.

HSI: Can you give us an example where OOC is used to generate safety data and show its value?

Lorna Ewart: According to current regulatory guidelines, candidate drugs are required to be tested in two animal species, typically a rat and dog, when considering small molecules.

In November 2019, Emulate published in Science Translational Medicine, describing the simultaneous development of rat, dog, and human Liver-Chips. We demonstrated that species chips were able to reproduce species-specific toxicity, importantly highlighting where chips could highlight toxicities that were not relevant to human, therefore enabling a candidate drug to progress but equally showing that toxicity detected in human Liver-Chips should be considered very carefully before progressing to a clinical trial. Regulatory authorities are very interested in understanding how this technology can be used to generate more human-relevant data like this.

To my knowledge, there has been no declaration of any pharmaceutical companies stating the use of OOC instead of animal models for safety testing. But I believe it will happen.

HSI: How is OOC replacing animal testing?

Lorna Ewart: I see that OOC has a role in each of the categories of the 3Rs: Replacement, Reduction and Refinement.

Reduction is probably the first example where OOC will impact. Emulate recently completed the single largest Organ-Chip study to date where we evaluated the performance of the human Liver-Chip across 27 small molecules that had been in the clinic. Liver-Chip was able to detect 9 out of 10 drugs that resulted in clinical hepatotoxicity. As such, we propose that scientists should adopt this model and use it before dose range finding studies in animals. By doing this, scientists can identify hepatoxic drug candidates earlier in their screening cascades. They would therefore not need to perform the in vivo study for this candidate, thus reducing the number of animals used. Ultimately, as more organ chip models show a high predictive value for clinical outcome, conversations about the steps towards replacement of animals can begin.

Refinement may be a little harder to demonstrate but it is possible to use OOC to understand the exposure ranges and therefore avoid exposing animals to unnecessarily high doses of the candidate drug.

HSI: Do you see researchers moving away from animal testing? What’s your perspective on this?

Lorna Ewart: I sense that there is growing momentum in the field of animal model alternatives. I believe we are in very exciting times, perhaps at the tip of the iceberg with growing voices from younger scientific generations questioning the validity of animal testing, especially as technology continues to advance.

Governments can also play a major role. Korea’s PAAM Act will help accelerate the acceptance and use of NAMs. Discussions in the European Union are also pushing scientists to think differently. It’s not going to happen just through one organization, one scientist alone. It’s partnership work.

HSI: Regarding the role of government, do you have any suggestions how Korean government can encourage the OOC field and move towards non-animal approaches?

Lorna Ewart: Firstly, the technology has huge potential, but the field needs further investment to continue to improve it and realize its full value. If the Korean government can consider targeted investment towards non-animal alternatives such as human relevant models, it would drive the field forward.

Additionally, government can also proactively encourage the use of new technologies especially when it comes to developing pharmaceutical products. This can be done by positively choosing to use alternatives rather than accepting the traditional norm of animal testing.

HSI: Regarding Korea’s PAAM Act, how do you think it will contribute to advancing science communities?

Lorna Ewart: Researchers will be able to use the best tools available to them, instead of being limited by animal models, which are known to have translational issues. By reducing our global reliance on non-human testing methods and instead leveraging human biology for human drug development, we anticipate the combination of human biology and technology to usher in a new era in human health.

Reference in this article to any specific brand, trade, firm or corporation name is for the information of the public only, and does not constitute or imply endorsement by Humane Society International or its affiliates of any specific company or its products or services, and should not be construed as or relied upon, under any circumstances, by implication or otherwise, as investment advice. The views and opinions expressed in the article do not necessarily state or accurately reflect those of Humane Society International or its affiliates.